Navigating Rates

Economic outlook: three trends to watch next

Recent difficulties in the banking sector have underlined the heightened risks of financial "accidents" as the world economy adjusts to an era of higher interest rates. With a high likelihood of a recession later in 2023, investors may need to prepare for more financial stress flashpoints as some of the excesses of a period of easy money are unwound.

Key takeaways

- Higher interest rates have played a role in fuelling recent banking-sector difficulties following years of very low rates – and further financial “accidents” cannot be ruled out.

- The peak of the financial cycle – seen most recently in 2021-22 – has historically pointed to a risk of recession and heighted financial-sector stress.

- “Moral hazard”, where riskier behaviour is, in effect, incentivised, has also emerged as a fresh dilemma for markets in the wake of recent bailouts and other support packages for banks.

- We think investors can expect further headwinds for risk assets – including rising volatility in equity markets, and a less certain outlook for fixed income.

A series of recent banking scares are posing an unsettling question for investors, central banks, and regulators: are the crises primarily idiosyncratic risks or is there cause for greater concern?

It is true that each of the banks in the headlines had its own specific problems. Of the most high-profile cases, California-based Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) became a victim of a badly managed asset-liability mismatch. First Republic Bank – the focus of continuing rescue efforts – suffered from a large base of concentrated and uninsured deposits. Fellow US banks Silvergate and Signature suffered from exposure to the crypto world.

Meanwhile, Credit Suisse has underperformed the banking sector for several years already, following losses related to the collapse of Archegos Capital Management and Greensill.

These are not the only recent “accidents” in financial markets. Last September, UK pension funds suffered a liquidity crisis due to margin calls around their liability-driven investments strategies in the wake of the government’s mini-budget, while crypto exchange FTX collapsed in November.

Investors seeking to make sense of these episodes are again pondering the question of “moral hazard”. Do signals of government support – such as those measures that rescued Credit Suisse and SVB – disincentivise investors from guarding against risk?

Do rising interest rates mean increased financial pain?

All the above examples have unique characteristics. But we think there is a common factor that contributed to the troubles: rising interest rates in response to higher inflation after too much easing of monetary policy since the global financial crisis of 2007-8. The financial market deregulation of the last decade may also be partially to blame.

The latest and most extreme round of fiscal and monetary stimulus unveiled by governments after the Covid-19 pandemic prompted a rapid rise in credit growth. Private sector debt reached elevated levels and risk appetite among investors picked up sharply.

As a result, equity markets soared: the US equity market showed the characteristics of a bubble in 2021-22. New assets like cryptocurrencies and special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) emerged and established financial instruments such as private equity and venture capital boomed. These were potential symptoms of an overheating in the economy and financial markets.

Meanwhile, inflation surged in the wake of ultra-easy monetary policy as well as structural supply-side shocks. Major central banks responded – arguably too late – by raising rates forcefully.

Then everything changed. With the rising rates and tightening in financial conditions of 2022 and early 2023, the world economy entered a period of readjustment and rebalancing as some of the earlier excesses were unwound. As so often in the past, this process can lead to financial “accidents”.

Economic and financial market rebalancing

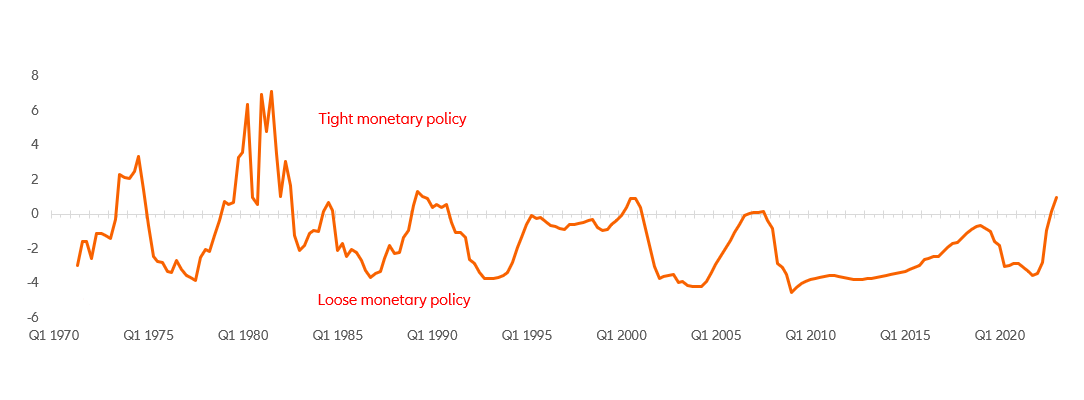

Exhibits 1 and 2 illustrate the link between financial conditions and financial crises over the past half century. The line in Exhibit 1 shows the difference between the real US Federal Reserve (Fed) funds target rate relative to our estimate of the so-called neutral rate – ie, the interest rate at which the economy is growing at the trend growth rate and inflation is stable.

Periods of ultra-easy monetary policy have been conducive to an overshooting of asset prices, not only in the US but sometimes in other parts of the world. The international spillovers are not too surprising as the Fed is the most important central bank globally and other central banks are “importing” US monetary policy via an explicit or implicit peg of their currencies to the USD.

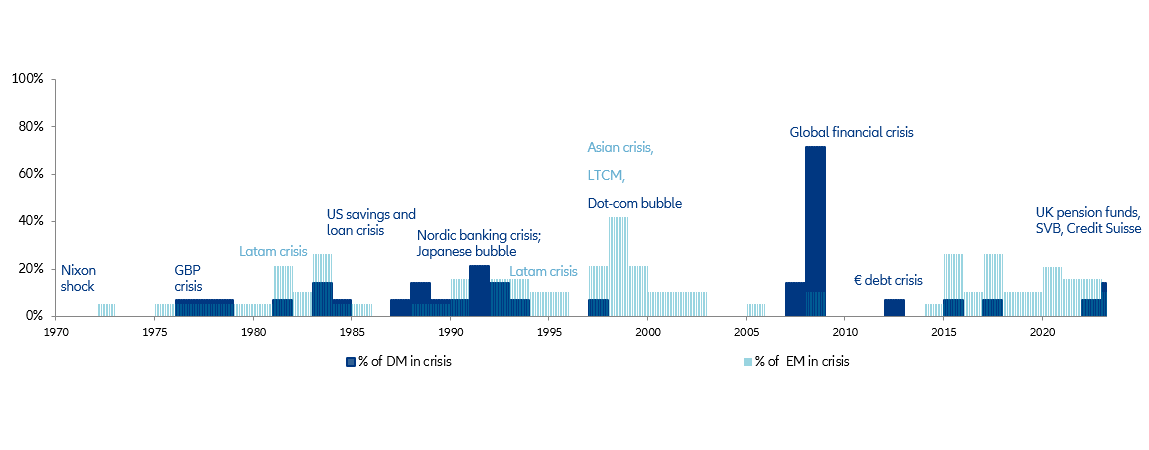

Once the Fed started to tighten, financial crises – such as bank failures, government debt defaults or major currency devaluations – often followed with a lag.

Exhibit 1: real fed funds target rate relative to neutral in %-points

Exhibit 2: share of countries in financial crisis

Source (for both exhibits): AllianzGI, BIS, Refinitiv, crisis definition following Leaven/ Valencia, Schularick/Taylor, Nyuyen/Castro/ Wood, own estimates, Financial Cycle estimate as at Q1 2023, financial crisis as at March 2023

In other words, the recent financial “accidents” should perhaps not come as a surprise. It is, however, to some extent surprising to see casualties primarily in the banking sector. Banks were perceived as better capitalised than they were before the global financial crisis.

In its October 2022 Financial Stability Report1, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) highlighted risks in the non-bank financial sector. Why? Because non-bank financials have increasingly won market share in the credit business following the global financial crisis and some areas are less tightly regulated.

The real estate market is the other major source of financial stability, according to the IMF. Real estate prices and valuations have overshot in many markets between 2020-2022.

Our analysis last year already showed similar conclusions. The financial cycle – which measures the joint dynamics of house prices and private sector leverage – topped out in 2021-22 in many economies and globally. Historically, a peak in the financial cycle has not only indicated a recession risk with a probability of 90% or more, but also a heightened risk of stress in the financial system.

Worst over or more to come?

As of now, it is difficult to say whether we have already seen the worst or if more is to come. We cannot exclude more episodes of stress, particularly as a recession later in the year remains a highly likely scenario – as suggested by inverted yield curves and contracting money supply numbers.

So far, the financial accidents have turned out to be just that – “accidents” rather than the start of a systemic crisis. In these instances, coordinated intervention by central banks, regulators and private banks may have contained the spillover effects.

In addition, various indicators of financial stress – such as the US Treasury-EuroDollar (TED) spread or the European Central Bank’s Compositive Indicator of Systemic Stress (CISS) for both the euro area and the US – remain well behaved.

While we take some comfort from these numbers, financial stress indicators tend to have a poor record as an early warning signal. They tend to be “coincident indicators” in that they reflect the current status of the economy rather than its trajectory.

What to expect now

Given the macroeconomic outlook, we think investors would be wise to expect the following:

- Equity market volatility may increase further. We think that equity market volatility, which has so far only risen moderately may rise further – in contrast to the already more-pronounced bond market volatility. Uncertainty about the current environment is high. Our data indicates that equity market volatility usually follows monetary policy tightening and the flattening of the yield curve with a time lag, and therefore it would make sense for it to be elevated now.

- Investors will likely demand higher risk premiums. This would point to further headwinds for risk assets. Moreover, we would also expect banks to become more risk averse in their loan book, which exacerbates the risk of an economic slowdown.

- Interest rates may still rise. If a systemic crisis can be avoided, central banks will have to “cover more ground” to get inflation under control – to quote Fed chair Jay Powell and European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde. This could point to higher interest rates and sovereign bond yields compared to current levels. Bear in mind that higher rates could trigger further “accidents”.

By contrast, if central banks decide that financial stability concerns warrant less monetary policy tightening – or even interest rate cuts – bond yields could fall substantially. By how much and for how long is unclear, as there is a clear risk that medium to longer-term inflation expectations would possibly pick up in such a scenario.

Finally, if recent bailouts and further government support do set in motion a fresh round of “moral hazard”, markets may react positively in the near term. But we know that there is a price to be paid at some point in time in the future.