Navigating Rates

Office real estate – medium-term headwind?

For many white-collar workers in the West, one of the enduring changes brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic was a change in workplace location. According to data from the Survey of Workplace Arrangements and Attitudes, before the pandemic fewer than 5% of US workdays were taken from home. After peaking at 60% in the early weeks of the pandemic, this remains at nearly 30%. This drastic change in working patterns is causing a profound shift in demand for office space.

Key takeaways

- The change in working patterns caused by the pandemic has led to a significant revaluation of office real estate.

- Given the sharp increase in financing costs, a fair question to ask is if whether commercial real estate (CRE) can create significant risk in the US financial system and specifically for banks.

- Unlike in past real estate crises, this time the exposure of large US banks is low. Risk appears to be concentrated in smaller banks, although granular disclosure here is limited.

Cushman and Wakefield report that, by the second quarter of 2023, nearly one fifth of US office space was vacant1, a dramatic increase from the roughly 13% vacancy rate before the pandemic. The increase in vacancy rates shows no signs of slowing, and is likely to increase further. As leases come to an end, firms will make adjustments to their real estate footprint to accommodate this shift in working patterns.

The rising vacancy rate, combined with the significantly higher interest rate environment, has led to a large reduction in commercial real estate (CRE) values, particularly for office. The total value of US office CRE is estimated to be around $5tn, although some analysts believe that this value could decline by more than one third in the coming years. Unlike some previous crises, the losses this time will likely be spread widely. Disclosure around who the ultimate owners of US office real estate is patchy. While REITs and Private Equity firms are large owners of commercial real estate, most of their exposure is outside the office area. While a quarter of REIT assets were office at the turn of the millennium, by 2021 that had shrunk to around 5%. Likewise, the largest private equity firm globally, Blackstone Inc, recently reported that US office represents less than 2%1 of their real estate portfolio, down from more than 60% in 20072.

Many of the assets have been picked up by pension funds, endowments and foundations, who likely own a majority of real estate. These investors typically have around 10% allocation to real estate, and some of the largest have begun to write down the value of their real estate in response to the weakening market. However, after years of strong returns from equities and alternative assets, and with limited near-term cash requirements, these value reductions are likely to be manageable for these investors. In the past, banks have had significant exposure as lenders. Banks have often been significant enablers of real estate booms – extending larger and larger loans supported by ephemeral valuations of the underlying real estate – before suffering significantly in the aftermath. The Global Financial Crisis in 2007-9 is the most prominent recent example of this. However, such an outcome is less likely this time: the largest US banks have kept exposures down, with almost all reporting that office exposure represents less than 4% of their loan books, and that these loans were more conservatively underwritten than CRE loans written before the Global Financial Crisis, with loan-to-value ratios below 60% and good debt service cover. To date, the impact on banks has been small: reported losses on office CRE loans have been minimal, although delinquency rates on loans have nearly tripled from the low levels seen in late 2022.

So, if not with the large banks, where does the risk lie? Within the financials industry, there are two areas at most risk from large loans to real estate. The first is at smaller banks (those with less than $100bn of assets). These smaller banks, of which there are more than 4,000 in the US3, represent around a quarter of total US banking system assets, but are estimated4 to hold more than 70% of the bank loans to office and downtown retail CRE. Many of these loans were made relatively recently and at elevated property values, as these banks sought to deploy the huge inflows of deposits seen during the extraordinary monetary and fiscal stimulus deployed in response to the pandemic. According to Moody’s, the number of US banks with CRE concentrations in excess of regulators’ 2006 CRE guidance levels has increased from 300 to 700 in the last two years (implying more than one out of every 10 US banks has CRE concentrations in excess of supervisory guidance). These smaller banks will suffer two additional challenges. First, in many cases their office loans are concentrated in a small number of markets. While nationwide office vacancy rates are close to 20%, the vacancy rate is much higher in major cities like San Francisco, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, as well as some regional markets. The exact location of the underlying buildings matters, and some banks will have large exposures to particularly challenged markets. Second, in many cases the loans these banks have made are too small to be of interest to non-bank lenders, preventing these banks from exiting problem loans. The challenge for investors is to assess which of the 4,000 banks have large exposure, as disclosures on this matter vary significantly by firm.

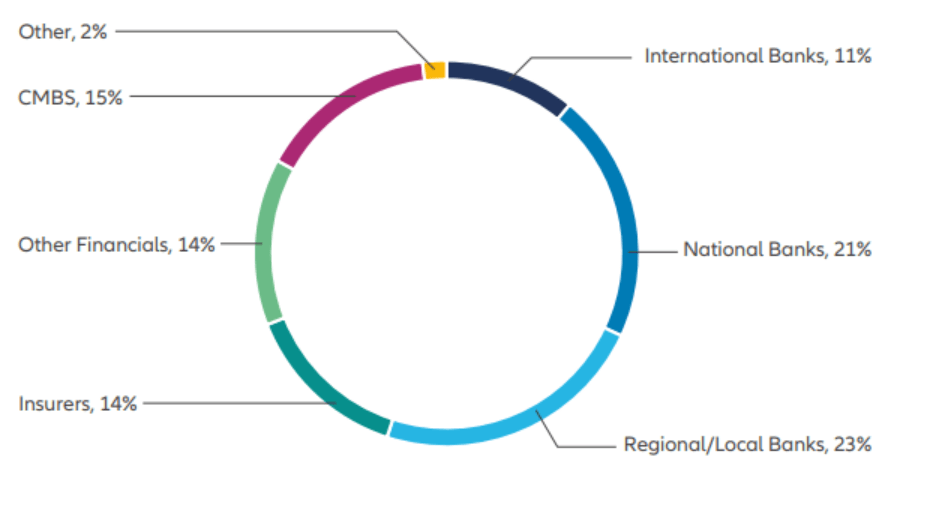

Office CRE Lender Share

Source: Morgan Stanley (March 16, 2023), Real Capital Analytics

The second sector most at risk is life insurers. Real estate as an asset class is attractive to this investor type: with large amounts of long duration customer capital, real estate and loans to real estate represents a long duration, asset-backed asset class. Based on estimates from Jefferies, the largest life insurers have around one sixth of their investment assets invested in CRE. However, because of the high leverage embedded in life insurers business models, the real estate exposure approaches 200% of statutory capital. Like the large banks, the large life insurance companies have reported that they see the risk as being low, with loans to value on office loans around the 50-60% level and with the loans well covered by rental income. These metrics will likely continue to deteriorate, but the risk to the life insurers looks low.

While losses might be large, they will be widely dispersed and are likely to be realised over many years, as the vast majority of real estate loans mature beyond 2025. Borrowers and lenders have time to resolve problem loans, which will be a key focus for many institutions in the coming few years.