Achieving Sustainability

Liquid capital: how investors should tackle the water crisis

Water is essential to life – it is also sometimes a threat to life. With both droughts and floods likely to increase as temperatures and global populations rise, significant work is needed to mitigate and adapt to these risks. We expect investors to intensify their focus on water – whether they are screening portfolios for water risks or identifying the providers of possible solutions to the water crisis.

Key takeaways

- In 2022, some of the most extreme water events in history – both in terms of droughts and floods – hit the headlines.

- Water is increasingly being recognised as a prominent physical risk, with significant economic and social costs.

- Water security touches on many environmental and social sustainability goals, including all the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goal targets.

- Water-related risk and opportunity screening is likely to escalate significantly in 2023.

Water is not only essential for human life but also for the global economy. Yet this seemingly abundant resource is under threat. Most of the water on Earth is unfit for human consumption or locked in glaciers. Only 1% of water resources are available as freshwater.1 In addition, water remains unevenly distributed across the planet. As a result, billions of people are living without safely managed water and sanitation. It is estimated that half the world will live under water-stressed conditions by 2050 unless we adopt an integrated and inclusive approach to restore the balance.2

This paper addresses the importance of understanding the full extent of the planetary, social and economic implications of water as a resource and the role investors can play in mitigating risks and providing solutions.

Water security is targeted by Goal 6 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that aims to ensure access to clean water and sanitation for all by 2030. Despite some recent progress, we are still far from reaching this goal, which intersects with other SDG goals such as poverty reduction, food security and human health. In addition, the increasing global water crisis poses potentially significant financial risks: a recent study showed that water-related natural disasters could hit global GDP by USD 5.6 trillion by 2050.3

The worsening water crisis

Global water use is increasing faster than population growth. In fact, over the past century, global water use has increased at more than twice the rate of population growth.4 While the global population is projected to rise 21% from the present 8 billion to 9.7 billion in 2050,5 global water demand could rise by 20–30% over the same period.6 A combination of increasing demand and water pollution is pushing some regions to reach their water resource limits, heightening related social risks. At the current rate, twothirds of the world’s population may face water shortages.7

There are three elements to the water crisis: water scarcity, water stress, and water risks.

Water scarcity

This is when water demand exceeds availability because water supplies can be limited for several reasons.

Water stress

Water stress covers water accessibility and quality in addition to availability. Water stress potentially poses a global systemic risk to every sector and economy around the world. In addition to direct operational risks, businesses face physical, regulatory and reputational risks.

Water risks

When water stress combines with non-stress related factors (eg, climate change or natural disasters), this aggregates into a risk measure of the severity and likelihood of being unable to source water from a particular watershed/basin. (see exhibit 1.)

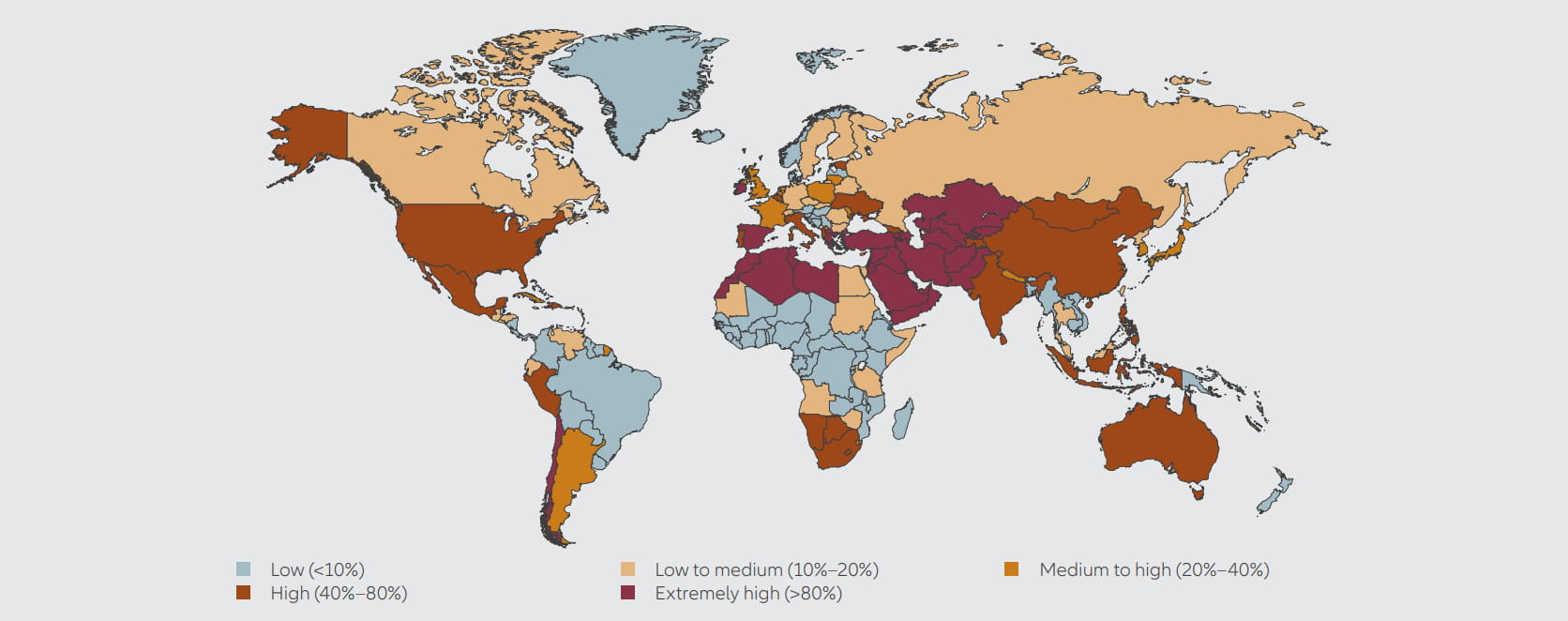

Geographically, some areas are more exposed to water stress than others. For example, the Middle East is likely to be the most affected area by 2040, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI).8 Kuwait, Palestine, Qatar, Israel and Lebanon are among those nations that draw heavily on groundwater and desalinated sea water. As the sourcing of such resources can be significantly exposed to geopolitical factors, including conflicts, these nations risk experiencing high water stress by 2040. The US, China and Australia are projected to experience a significant increase in water stress in the future. The WRI study also highlights that growing competition for access to diminishing resources could prompt political, geopolitical and economic tensions.

Exhibit 1: Understanding water scarcity, stress and risks

- Physical risk encompasses water quantity and quality issues and represents a major threat for waterintensive sectors like apparel, food and beverages, and agriculture.

- Regulatory risk is related to the potential for local authorities to impose stricter regulations, limit use or increase the pricing.

- Reputational risk is linked to the potential brand value damage coming from the perceived negative impacts on the quantity and/or quality of water resources.

Source: Allianz Global Investors

Water crisis is inextricably linked to climate change

The most undervalued resource on Earth?

Water scarcity has social costs

Today, 2.1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, and more than 3 million die each year from water-related diseases.9 In addition to the direct impact on mortality, the lack of access to safe and affordable water threatens food security, social well-being, education, and the ability to break away from the vicious cycle of poverty.

Water distribution is extremely uneven around the world, and it is only getting more so. In 2022, at the same time as many areas faced record and extreme droughts, others suffered intense flooding. In Pakistan, for example, the devastating floods affected 33 million people, put onethird of the country under water and displaced a minimum of 7.9 million people, according to the UN Refugee Agency. If these conditions continue, it is estimated that 1.2 billion people could be forced from sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East to migrate to Europe and North America by 2050.10

Despite some progress, significant challenges threaten to undermine the promise to “leave no one behind”11 and ensure equality of access to basic water and sanitation services. Addressing the challenges of SDG 6 requires the integration of a human rights-based approach. Water access must be viewed as a fundamental human right and not simply a commodity to be managed.12

Spotlight on groundwater: vital but undervalued

Groundwater makes up 99% of the Earth’s available freshwater and is the source of half the world’s drinking water, securing water needs in low-income regions. However, climate change directly affects the water cycle and the availability and quality of freshwater below ground. It is estimated that 44% of all aquifers – underground water supply – will be depleted because of climate change in the next 100 years.13

Exhibit 2: Water stress by country (2040 forecast)

Source: World Resources Institute aqueduct water risk atlas

Water flows into financial performance

Awareness appears to be increasing about how water – both the scarcity and excess of it – can have a significant economic impact on companies. Agriculture is an obvious example, but many industrial activities are also heavily reliant on water. A less obvious example is the semiconductor industry. For instance, in 2021 Taiwanbased factories had to reduce production due to droughts and use tankers to provide water.14 In turn, this raised tensions with farmers, who suffered the same issue but had to share this constrained – though vital – resource.

How should investors quantify these impacts? While data continues to evolve, one relevant key performance indicator (KPI) would be the water intensity of the production process. But getting this data might be hard, and the resulting figures may not be exact. Nor does this data tell the whole story: sectors such as finance and energy have indirect exposures to water. For example, finance companies may have a high revenue exposure to sectors with an aggregated high exposure to water risks. In the energy sector, hydropower is evidently reliant on a direct supply of water, while nuclear and thermoelectric plants require significant amounts of water for cooling. These dependencies were evident in the summer of 2022 in France when the drought impacted the functioning of dams and power plants.15 We hope and expect that the understanding and measurement of water materiality in sector and company profiles will increase.

Absorbing water into investments

Genuine thirst for innovation

1 WWF, 2022, Freshwater

2 MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change 2021, Global Change, 2021 Outlook

3 GHD, 2022, Aquanomics: The economics of water risk and future resiliency

4 United Nations, 2018, Water Scarcity

5 United Nations, 2022, Revision of World Population Prospects

6 nature partner journals, 2019, Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report

7 WWF, 2022, Water Scarcity

8 World Resources Institute research, 2015, Acqueduct projected water stress country rankings

9 World Health Organization, 2022, Drinking Water

10 Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), 2020, Launch of the inaugural Ecological Threat Register

11 UN, 2015, 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Leave no one behind is the central, transformative promise of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals.

12 The human right to safe drinking water and sanitation was first recognised by the UN General Assembly and the Human Rights Council in 2010, although this vote is not legally binding (see: European Parliament, 2021, The Human Right to Drinking: Impact of large-scale agriculture and industry)

13 UN, 2022, World Water Development Report: Groundwater: Making the invisible visible

14 Forbes, 2021, No Water No Microchips: What Is Happening In Taiwan?

15 World Economic Forum, 2022, 5 unexpected impacts of drought in Europe

16 PAI biodiversity factors are activities negatively affecting biodiversity-sensitive areas, emissions to water and hazardous waste and radioactive waste ratio

Water risk materiality

For investors seeking unconstrained universes, it will be important to identify material ESG risks relating to the water impact on companies and sectors, including:

- Water intensity: there is rising scrutiny of water usage and management, especially for regions at high risk of droughts or floods. Water intensity is nuanced given the intensity, availability and reliance factors across a company’s supply chain.

- Physical risks: the proportion of revenues, earnings or assets in locations with severe or very severe risk of droughts or floods.

- Controversies are always an indicator, but these will mostly highlight companies with direct exposure to water issues (through local pollution incidents or overuse) without revealing issues related to water dependency across the extended value chain.

As mentioned earlier, water risks take on different forms and require a thorough understanding of a company’s entire supply chain, the locations of those activities, and the governance around those risks. In addition, controversies related to water pollution are becoming headline news, which can translate into negative risk performance.Regulatory screening

MiFID II and the formal Principle Adverse Impact (PAI) or Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) screens were all introduced by European Union regulators in 2022. Three of the 14 PAIs on sustainability factors are specifically aligned to biodiversity factors16 with one of these specific to “emissions to water”. However, water also touches on the notions of negative biodiversity impact and waste management. Alongside the disclosure regulations from the EU, there will be evolving country-specific and investor-led demands, as well as higher expectations on risk and opportunity governance for companies.

Impact-focused investing

Given all the challenges, there is a significant sustainability (and financial) opportunity in developing new solutions and technology to address the different water challenges. These opportunities include: